Contact Mark at Encyclopedia Sabrina

The Steve Cochran PageUsing material lovingly borrowed from https://frombeneaththehollywoodsign.com/f/steve-cochran-hollywoods-original-bad-boy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Cochran Youtube https://shadowsandsatin.wordpress.com/2012/03/10/gone-too-soon-steve-cochran/ https://www.sfgate.com/sf-culture/article/strange-death-of-steve-cochran-17520541.php |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ten Things you should know about Steve Cochran (Youtube) Robert Alexander Cochran (named after his father)Born: 25 May, 1917, Eureka, California, U.S. Died: 15 June, 1965 (aged 48) Off the coast of Guatemala Alma mater: University of Wyoming (for 1 year) Occupation: Actor, 1944–1965 Wives

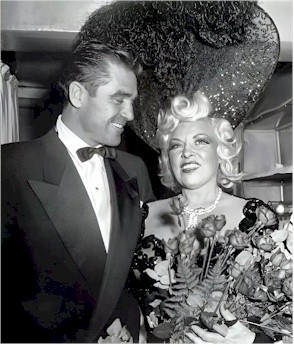

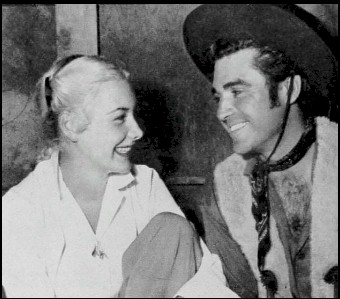

Children: one daughter, Xandra, with Florence Lockwood. He and Xandra became estranged. The Cochran family moved to Wyoming when he was a child. After stints as a cowboy and railroad station hand, he studied at the University of Wyoming for one year, where he also played basketball until he was kicked off the team for either missing training, or fraternizing with the opposite sex (or probably both). He quit college in 1937 to become a movie star. Cochran was rejected for military service in World War II because of a heart murmur, but he directed and performed in plays at various Army camps. Acting CareerHe was appearing with Constance Bennett in a touring production of Without Love in December 1943 when he was signed by Sam Goldwyn On Broadway, Cochran appeared in Hickory Stick (1944). Samuel Goldwyn brought Cochran to Hollywood in 1945. He loaned Cochran to Columbia Pictures for Booked on Suspicion (1945). Goldwyn then put him in Wonder Man (1945), playing a gangster. Columbia then used him in another film, Blackie's Rendezvous (1945), in which he played a villain, and in The Gay Senorita (1945) with Jinx Falkenburg. He then played in The Kid from Brooklyn (1946), and another gangster in The Chase (1946). Following that, he appeared in the prestigious drama The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), playing a man who has an affair with a woman played by Virginia Mayo that continues even after her husband (played by Dana Andrews) returns from war. He appeared with Groucho Marx in Copacabana (1947) and returned to gangster roles in A Song is Born (1948). He made his TV debut in "Dinner at Antoine's" (1949) and "Tin Can Skipper" (1949). He returned to Broadway to support Mae West in a shortlived revival of her play Diamond Lil. This revived Hollywood's interest in him. In 1949, Cochran went over to Warner Bros., playing Big Ed Somers, a power-hungry henchman to James Cagney's psychotic mobster in White Heat (1949) opposite Virginia Mayo. Cochran supported Joan Crawford in The Damned Don't Cry (1950), after which he was given his first lead role, in Highway 301 (1950), playing a gangster. He was a villain to Gary Cooper's hero in Dallas (1950) and a Ku Klux Klan member in Storm Warning (1951) with Ginger Rogers and Doris Day. Cochran was a villain in a western, Canyon Pass (1951), and the lead in Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison (1951). Many movie and TV roles followed, including going to Germany to make Carnival Story (1954). Back in Hollywood, he appeared in:

Cochran then went to the UK to play the lead in The Weapon (1956). Cochran supported Van Johnson in Slander (1957), and went to Italy for seven months to star in Il Grido (1957). On TV he appeared in

He played the lead roles in Quantrill's Raiders (1958), and in I Mobster (1959). Albert Zugsmith used him for the lead roles in The Beat Generation (1959) and The Big Operator (1959). After 1959, Cochran worked mostly in television shows and TV movies. Cochran was Merle Oberon's co-star in Of Love and Desire (1963), shot in Mexico. He had the lead in Mozambique (1964) for Harry Alan Towers. In 1953, Cochran formed his own production company, Robert Alexander Productions, which attempted to make some television series, and films such as

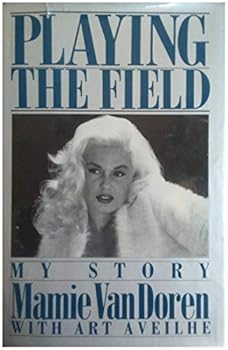

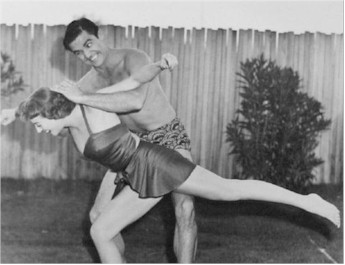

None of these was ever produced, but his company did make a television pilot, Fremont the Trailblazer, in which he played John C. Frémont. Cochran also wrote, produced, directed, and starred in Tell Me in the Sunlight (1965). Personal lifeCochran was a notorious womanizer and attracted tabloid attention for his tumultuous private life, which included well-documented affairs with numerous starlets and actresses. For example Mamie Van Doren later wrote about their sex life in graphic detail in her tell-all autobiography Playing the Field: My Story (1987).

He was married and divorced three times to actresses... Florence Lockwood (married 1935-1946)

Fay McKenzie (married 1946-1948, she died aged 101),

Jonna Jensen (married 1961-his death). She was a Norwegian immigrant whom he met when he was 44 and she was 19

Steve Cochran's Weird DeathCochran recruited three young Mexican women ... EVA MONTERA CASTELLANO (25), EUGENIA BAUTISTA ZACARIUS (19) LORENZA DE LA ROSA (14) to accompany him on a sailing trip on his 40-foot schooner, The Rogue, from Acapulco to Costa Rica, ostensibly to to scout locations for the upcoming film. Stopping in Acapulco. Cochran paid them 70 pesos a day (about $30 in today’s money) and offered them food, candy and access to his mini bar. They said they never touched the liquor. The trio told reporters that the actor was friendly and joked with them over dinner, and he promised to pay their way for a return journey if they chose to leave. Cochran would drink several whiskies every night and sleep under the stars on the deck, before making his way down to the cabin in the early hours. The yacht lost one of its two masts in a storm a few days into the trip. The crew said that while attempting to fix the mast, the actor complained of pain in his legs, which soon spread to his chest, arms and head. With his fever rising, Cochran became bedridden, stowed away in his cabin. Broken jars were strewn around his bed from the storm. The trio later recalled some of his utterances in his fever dream, including "Please don’t leave me alone” and "God, what will happen to you should I die?” Cochran reportedly asked his helpers to massage him to ease the pain. He also started giving them advice on how to sail the boat if he died, which included guidance to head due east and tie a red flag to the mast. The women with him said Cochran became paralysed and could move only his head. Then, on June 15, with only 14-year-old De La Rosa at his side, Cochran took his last breath. As Castellanos recalled, "Mr. Cochran died almost in the arms of Lorenza who had been bathing his fevered face with a wet towel.” She described the moment as one of relief. " "Mr. Cochran finally stopped complaining. He let out a deep sigh, he opened his eyes, and then he no longer complained.” After nine days adrift with a corpse, eating only potatoes, the female crew ran out of drinking water. A rainstorm that night provided some small hydration. On the 10th day aboard with the famous corpse, the helpless crew scanned the horizon and saw the silhouette of a ship. They violently waved their arms. Their savior came in the form of an American-owned fishing vessel named Bella de Portugal. Their 10 torrid days on the Pacific had come to an end. The Rogue was found drifting off the coast of the Guatemalan port town of Champerico on June 25 and was towed ashore. There, locals discovered the unsavory scene aboard. Moving the actor’s body was an unenviable task. "The huge blackish mass he had become disintegrated when the funeral home employees touched it,” reported Prensa Libre. "The stench of death washed over the small town.” Castellanos, Zacarias and De La Rosa were held for questioning before being turned over to the Mexican Embassy and flown home to Acapulco without charge. As the newspaper put it, they were still "affected by the stench of the decomposing body of the famous American film actor.” Cochran’s body was put in a zinc coffin and flown to Guatemala City along with the boat by the country’s Air Force for further investigation. There, medical authorities deduced Cochran died of a mysterious lung infection that also caused paralysis. One report said the medical examiner in Guatemala City who did the autopsy knew the actor. The description of paralysis of some kind was backed by the women and girl, who said the actor was only able to move his head while bedridden in the cabin. Rumors soon swirled of poisoning at sea. The LA Times phoned the police in Guatemala, only to be told that the authorities had no idea what caused the lungs to swell. The paper characterized the diagnosis of a lung infection followed by paralysis as a "mysterious ailment.” Much of the mystery came from a lack of coverage in the press. While Hollywood’s studio system was already falling apart, so-called fixers in the industry were still hard at work burying unwanted scandals. This may be why Cochran’s sensational death found few inches in the press at the time and isn’t well remembered to this day, while Natalie Wood’s mysterious death at sea in 1981, for example, made global front pages and headline news. At the time of his death, Cochran was technically still married to a woman named Jonna Jensen Cochran. By 1965, their marriage was over for all intents and purposes, possibly due to Cochran’s fondness for sailing the seas with underage girls. Jensen had filed for divorce from Cochran the previous year, but the case was never finalized, meaning that despite the protests of Cochran’s mother, Jensen inherited his entire estate. Cochran’s body was flown to San Francisco and buried next to his father, near the ocean in Monterey. His reputation was so tarnished that an old friend saw the need to defend his standing in a curious article in the Van Nuys News. Published two weeks after his death, actress and columnist Jeanne Markham Keating characterized Cochran as a kind and extremely good-looking man who was sadly a target for "numerous kooks who seemed to spot an easy mark.” Keating’s glowing ode to her friend, though, did end in referring to him as "an unusual and a different sort.” It is not clear what became of Castellanos, Zacarias and De La Rosa after their ghoulish brush with American celebrity and return to Acapulco. There is no evidence to suggest that Cochran was met with foul play on the yacht, and we will never know the actual responsibilities required of the girl and young women aboard. It is probably safe to deduce that it wasn’t all plain sailing aboard The Rogue, even before the actor’s demise. The three Mexicans told Prensa Libre that after Cochran chose his 10 crew members from the 100 applicants in Acapulco, seven resigned after meeting the actor and learning more about their duties. Shortly after his death, the LA Times spoke with an actress named Sandra Danielson, who had also once been invited onto Cochran’s boat to star in a movie. "You are supposed to speak well of the dead,” Danielson said, "but he put me in a very compromising situation. I told him I didn’t need a job that bad.” Cochran of an acute lung infection on 15 June 1965, at the age of 48. As Cochran rapidly turned into "a swollen monstrous thing” and a "fetid odor enveloped the yacht”, the only food left on the vessel was potatoes. The inexperienced crew members tied a red flag to the remaining mast, as they were instructed, and prayed the boat would drift ashore or help would find them. They did not know how to sail a boat and were trapped with the decomposing body for ten days before being rescued out at sea. The boat, still carrying his corpse, was later found drifting off the coast of Guatemala by the Guatemalan Coast Guard on 26 June 1965. Cochran was identified by Dr Abel Giron, who knew Cochran. Dr Giron performed the autopsy and said he could not pinpoint the exact nature of Cochran's illness until he received a laboratory report but the lung infection caused paralysis. [Assoc. Press, reported in The Fresno Bee, 28 June 1965]

Info from https://projects.latimes.com/hollywood/star-walk/steve-cochran/ ... The passengers, all from Acapulco, said they met Cochran through an advertisement in a newspaper that said he was seeking young girls to work on his boat and play bit movie parts. The plot: a romantic captain sets sail with an all-woman crew. The working title of the script was "Captain O'Flynn." Cochran had previously looked for young female sailors closer to his Los Angeles home. One of them, Sandra Danielson, said after his death: "You are supposed to speak well of the dead but he put me in a very compromising situation. I told him I didn't need a job that bad." By the time he died at age 48, Cochran had long had a reputation as a swashbuckling ladies man. He rode a motorcycle around Los Angeles and kept a collection of offbeat pets including goats and monkeys and dog he claimed could play piano. In 1952, Cochran was sued for more than $400,000 [$4 million in 2024 money] by an ex-professional boxer he assaulted at a New Year's Eve party. "I knew Buddy Wright was an ex-fighter," he testified in court, "so I hit him with a baseball bat." (Ruben Salazar in the Los Angeles Times 28 June 1965) Cochran died with an estate worth $50,000 [$500,000 in 2024 money] and was buried in Monterey, California. Merle Oberon his costar in Of Love and Desire. pleaded with the LA police to look into his death. She feared foul play, but there was no inquest.

Reports from 13 June, 2025 11:05 AM reveal that he is still dead. Cochran has a star at 1750 Hollywood Boulevard in the Motion Pictures section of the Hollywood Walk of Fame. It was dedicated on February 8, 1960.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As rough-and-ready as the characters Cochran played on the big screen, they almost paled in comparison to his off-screen life. He loved women and booze and liked to party...hard. He had many run-ins with the law because of his bad-boy lifestyle. He was in the press for being the first person to get a traffic ticket for the erratic piloting of his private plane over Beverly Hills, where he was spotted flying too low and tipping his wings at houses. He was also picked up by the police for assaulting a man with a baseball bat, recklessly driving in his sports car, and reportedly tying up and beating aspiring singer RONNIE RAE who had come to his house to audition. Charges were later dropped on all accounts, as this was the era when studios protected their stars and many studios had the police on their payrolls.

Above: Ronnie Rae, after and before. His notorious womanizing often found him in trouble too. On more than one occasion he was accosted by the jealous husbands and boyfriends of women with whom he had affairs. He was even sued by one man for alienation of affection from his wife. Cochran often found himself in the tabloids for his affairs with his co-stars and other notable Hollywood starlets. It was once said that if Cochran made a movie with them, he likely bedded them. His list of conquests reads like a 1950s fan magazine:

Later in his career, when his star began to wane, Cochran formed his own production company, Robert Alexander Productions, where he began to develop projects he could produce, direct, and star in. While most of his projects never got off the ground, he was obsessed with a pet project called Captain O'Flynn, the lusty tale of a sea captain who sets sail with an all-female crew. In June of 1965, Cochran set sail aboard his yacht "The Rogue" to scout locations for the film. Stopping in Acapulco. He hired three young Mexican women, EVA MONTERA CASTELLANO (25), EUGENIA BAUTISTA ZACARIUS (19), and LORENZA DE LA ROSA (14), as his all-girl crew for research for Captain O'Flynn. A day out of Acapulco, they encountered a severe storm that damaged one of the ship's masts leaving the ship floating aimlessly at sea. After attempting to repair the mast, Cochran fell sick. The women cared for him as best they could, but he soon took a turn for the worse and died aboard the yacht. As it turned out, none of the women actually knew anything about boating. "The Rogue" continued to drift in the sea for 10 days with Cochran's decomposing body locked down below in one of the two sleeping cabins. The women were finally rescued off the coast of Guatemala. The women told authorities what happened but for years there were whispers and rumors of foul play and poisoning but no evidence was ever found to substantiate this. His autopsy revealed that he died of a lung infection at the age of 48. In the end, STEVE COCHRAN died as he lived.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What did Mamie van Doren say about Steve Cochrane?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After a year at Wyoming University, Cochran quit to join the Federal Theatre Project in Detroit, but although he later decided to try his luck in Hollywood, he couldn’t even manage to get a screen test. Undaunted, he stayed in California, gaining more experience through little theater groups; while appearing in one production, There’s Always Juliet, he adopted the name of one of the characters, and Steve Cochran was born. Returning to Laramie, Cochran produced a number of little theater plays, then traveled extensively during the next several years, performing in Shakespeare festivals and road shows from California to Maine. Between acting jobs, he made ends meet by performing various jobs, including firing the steam plant at a sand pit near Del Monte, California, and working as a private policeman at Macy’s department store in New York. After nearly seven years of futile attempts to make it into the "big time,” Cochran finally got his break in the mid-1940s, when the Theatre Guild in New York cast him in the lad in Without Love. Soon after, he caught the attention of producer Sam Goldwyn, who took an option on his services. Cochran toured Columbus, Ohio, Milwaukee, and Chicago in the play before hitting Los Angeles, where Goldwyn exercised the option and cast Cochran in a popular Danny Kaye vehicle, The Wonder Man (1945). He also appeared that year in two entries in the 'Boston Blackie' series, Boston Blackie’s Booked on Suspicion and Boston Blackie’s Rendezvous, in which he starred as a crazed killer who escapes from a lunatic asylum. In terms of box-office receipts, Cochran hit the jackpot in 1946, with featured roles in a pair of money-makers, The Kid from Brooklyn, and The Best Years of Our Lives, which won a slew of Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Also that year, Cochran leapt into the domain of film noir, portraying a suave racketeer in The Chase. Here, Cochran played Eddie Roman, who lives in an opulent Miami mansion with his unhappy wife, Lorna (Michele Morgan), and his inscrutable sidekick, Gino (Peter Lorre). In the next two years, Cochran made only two films, Copacabana (1947), and A Song Is Born (1948), a hit musical. Instead, he took time off to appear on Broadway with the legendary Mae West in the revival of Diamond Lil. Upon his return to California, he signed with Warner Brothers and was cast in his second film noir, White Heat (1949). In this top-notch feature, Cochran played Big Ed Somers, a rebellious, outspoken member of a gang headed by the psychologically disturbed Cody Jarrett (James Cagney) in which reviews termed him "excellent.” The following year, Cochran continued racking up the bad-guy roles with starring parts in Dallas, an above-average western starring Gary Cooper; Highway 301, a gritty cops-and-robbers saga, and Storm Warning, co-starring Doris Day and Ginger Rogers. In this gripping feature (which also starred president-to-be Ronald Reagan), Cochran played a bigoted family man who is a member of the Ku Klux Klan. He later called the role his favorite of his career. "To me, one source of satisfaction in playing the role of Hank in Storm Warning was the feeling that I might be making a small contribution toward racial tolerance,” he told the Saturday Evening Post. "As a youngster in Wyoming, I had seen the fiery crosses of the Ku Klux Klan burning near my home and even then I sensed their frightening menace. As Hank in this picture, I had a chance to show how basically shabby such demonstrations are.” Cochran’s final film of 1950 was his third film noir, The Damned Don’t Cry, with Joan Crawford, David Brian, and Kent Taylor. Here, Cochran was again cast as a gangster, this time playing a renegade syndicate member who tries to take over the entire organization from his ruthless boss. This well-made and often gripping feature earned mixed reviews, but there was no disagreement over Cochran’s performance – the critic for Trade Show said the actor "has a field day in a colorful spot,” Film Daily’s reviewer labeled him "vivid and compelling,” and in the Los Angeles’Times, Dorothy Manners wrote: "Next to [Joan Crawford], Steve Cochran makes the best impression as the diamond-in-the-rough who dares to break with the syndicate – and winds up just in the rough.” The year 1951 would be the busiest of Cochran’s career – the best of his five pictures that year were Jim Thorpe – All American, a biopic about the Native American Olympic star, and Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison, a prison film set in the 1920s, which starred Cochran as a tough inmate who leads an escape. Off-screen, though, Cochran became embroiled in the first of many brushes with the law.

During the next two years, Cochran played starring roles in six fairly forgettable films, and was featured in the dreadful musical The Desert Song (1953), which was his final film under his Warner Brothers contract. Meanwhile, in 1953, Cochran started his own production company, Robert Alexander Productions, and enthsiastically discussed his new venture in the press. "I left Warner Bros. recently because I wasn’t growing,” he said. "I had some pleasant assignments there ... but the last few parts were so bad I had to get out. This new producing-acting venture is my most exciting experience yet.” In 1954, Cochran starred with Ida Lupino and her then-husband Howard Duff in the tense film noir, Private Hell 36, produced by Lupino’s production company, Filmakers. Cochran played Cal Bruner, a police detective who, along with his partner (Howard Duff), finds a steel box filled with cash following a car crash. Rather than turning over the entire amount, Bruner talks his partner into splitting a portion of the money, which he craves, in order to provide material possessions to his nightclub singer girlfriend, Lili (Lupino). After portraying a seedy circus advance man in Carnival Story in 1954, Cochran was off screen for a year, returning instead to the stage, where he starred as Starbuck in a production of The Rainmaker. He was back to feature films in 1956 in Slander, a fast-paced drama that starred him as the ruthless publisher of a tabloid magazine. Then he was in Come Next Spring, the first film produced by Cochran’s production company. In this feature, Cochran starred opposite Ann Sheridan as a farmer who redeems himself for his past drinking and wild ways. During this time, Cochran also began appearing on various television programs, including Zane Grey Theater and The Naked City. Cochran was also busy making headlines for his off-screen exploits. In October 1956, he earned the dubious distinction of receiving the first flying ticket issued by a police helicopter. The adventure-loving actor – who had been flying for about two years, and had approximately 100 hours of flying time behind him – was cited by officers when he dipped over his mountaintop home in Studio City and rocked his wings. Claiming that he did not see the police helicopter trailing behind him, Cochran initially pleaded not guilty, but he later reversed his plea and was fined $500, grounded for 90 days, and given a suspended sentence of 30 days in jail. The actor was in only one film in 1957, a thriller entitled The Weapon, about a boy who accidentally shoots a playmate with a gun used to kill an Army officer 10 years before. He spent much of the year on a five-month, picture-making junket to Europe, scouting locations for his upcoming film project, Il Grido. The picture, in which Cochran co-starred with Alida Valli and Betsy Blair, was filmed and released later that year in Italy, but wasn’t released in the United States until 1962. Meanwhile, Cochran starred as a Confederate officer in Quantrill’s Raiders (1958), a low-budget western, and as an underworld kingpin in I, Mobster (1958), in which he suffered his 25th onscreen death. Shortly after the release of the latter film, Cochran discussed his success in playing villains on the silver screen: "I don’t act like a hood [in my films, I’m basically a decent person and I let this come through in my portrayals. After all, a guy has to make a living some way, even if he’s a gangster. The big secret in playing a gangster in movies is to really believe that the character you are playing is doing no wrong.” Cochran followed I, Mobster with a rare heroic role in The Big Operator (1959), as a man who goes up against a tyrannical labor boss, chillingly portrayed by Mickey Rooney. Cochran’s next film, The Beat Generation (1959), featured him as Dave Cullman, a woman-hating cop searching for a rapist.” The feature was a disaster at the box office and was slammed by critics. Words such as "downright embarrassing” and "excruciating and tasteless" were used. In 1960, Cochran had a brush with disaster when his yacht crashed into a Los Angeles Harbor breakwater in heavy fog. The actor and the boat’s other occupants – two young woman, two dogs, and a monkey – were forced to dive out of the boat and escaped without injury. It was the second sailing mishap of Cochran’s life. Several years earlier, he had spent a grim night in the Catalina Channel, bailing out his 35-foot ketch until a U.S. Coast Guard patrol boat towed the actor in. After two brief marriages earlier in his career, in 1961 married Danish actress Jonna Jensen in Las Vegas on March 18th. The two separated in November, and the actress filed for divorce on January 5, 1962. Meanwhile, Cochran was in television series such as The Untouchables and The Twilight Zone, and in big-screen features including The Deadly Companions (1961), and Of Love and Desire, (1963), that marked Merle Oberon’s return to pictures after a seven-year absence. In August 1964, while shooting his next film, Mozambique, in South Africa, Cochran was arrested on a civil court order brought by a local jockey who accused him of adultery. The jockey, Arthur Cecil Miller, sought $5,000 in damages, claiming that Cochran had been having an affair with his wife, who had a small role in the film. The following month, a high court judge cleared Cochran of all charges and threw out the jockey’s claim. Cochran angrily stressed his innocence, saying: "It didn’t happen and the fellow didn’t have a shred of evidence. He submitted what he said was a love letter [to his wife] from me. You know what it said? ‘To Heather, nice to have worked with you Aloha, Steve.’ I gave autographs like that to a number of kids who worked in the film.” Three months later a 23-year-old singer, displaying a bruised and swollen face, told police that Cochran had beaten and gagged her during a quarrel at his Hollywood Hills home. The singer, Ronie Rae, told authorities that Cochran invited her to his house to audition for a part in a new film he was producing, Captain O’Flynn. After she accidentally spilled a drink on Cochran’s floor, Rae claimed, a quarrel ensued, during which Cochran tied her hands and feet with neckties, beat her, and gagged her with a towel. She was able to eventually free herself and arrange for her father and grandmother to pick her up, Rae said. Cochran’s account of the incident was vastly different. He agreed that Rae was at his home for an audition, and he also admitted that he had bound her with neckties, but he said that it was for her own protection because she has "hurtling herself about.” The violence was initiated, Cochran stated, after Rae had consumed her second drink and took exception to the fact that the actor was ignoring a tape of her songs. "I didn’t want to embarrass her by saying, ‘Horrible. Awful. Can’t stand it. Go home!" he explained. So instead, he went upstairs, the actor said, and Rae threw herself to the floor, smashed furniture, and butted her head against the fireplace. "She appeared to be on some kind of pills,” Cochran said, adding that when her father arrived to pick Rae up, his first words were, "She’s been on those pills again.” Just five days after the news broke, Cochran was cleared of all charges. ln fact, officials declared that the actor may have done [Rae] a great service, by tying her up.” The film for which the actress was auditioning, Captain O’Flynn, was to be based on the real-life adventures of Lee Quinn, a ship captain who, in 1963, began a voyage in the Pacific aboard his ketch with an all-girl crew. Cochran was intrigued with the idea of bringing Quinn’s story to the big screen, and in 1965 he decided to enact a first-hand tryout of the adventure. Out of a pool of 180 female applicants drawn from an advertisement in local newspapers, Cochran hired three Mexican women, Eva Montero Castellano, 25, a seamstress; Eugenia Bautista Zacarias, 19, a laundress; and 14-year-old Lorenza de la Rosa, "as maids and helpers" to accompany him on an eight-day sailing trip from Acapulco down the Pacific Coast to Costa Rica, where the picture was to be filmed on location. Cochran and his crew set sail on 3 June 5, 1965. Three weeks later, on June 26, 1965, the actor’s 40-foot schooner was towed into the Guatemala port of Champerico. On board were the three women – and the dead body of Steve Cochran. Officials later determined that the 49-year-old actor had fallen ill from a paralyzing lung ailment during the voyage and died 10 days after departing from Acapulco. For nearly two weeks, the women drifted helplessly in the schooner before being rescued in Guatemala. Just four days after the actor’s body was discovered, his estranged wife, Jensen, filed a petition in Los Angeles Superior Court for letters of administration over his estate, estimated to be worth $150,000. The following day, the actor’s 79-year-old mother, Rose Cochran, filed a similar petition of her own, pointing out the fact that her son’s widow had filed for divorce. She also cited a post-nuptial agreement by her son and his wife which stipulated that all of their property was to remain separate. The agreement further stated that Jensen would receive one-third of his estate – only if there was no action pending for divorce for separate maintenance. In July, a Superior Court judge appointed both Jensen and Rose Cochran as temporary administrators of the estate, but three months later, Jensen was named sole administrator. After his death, Cochran’s last two films were released – Mozambique [1966], the picture he made in South Africa, and Tell Me in the Sunlight [1967], which marked the actor’s sole big-screen directorial credit.) This article is a version of the chapter on Steve Cochran that appears in the book, Bad Boys: The Actors of Film Noir.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Steve Cochran Is Real Cool Catby Rob Thomas Oakland Tribune, 27 December 1958 |

HOLLYWOOD, Dec. 27, 1958 - Those who think that Hollywood is losing its characters should take a trip up to Steve Cochran's house. Some place! It's got a swimming-pool that looks more like a mountain lake complete with island. Also 25 animals, including two goats and a deer named Taby. The Cochran place has to be seen to be believed. You go up Coldwater Canyon from Beverly Hills, turn at the top at the mountain, drive along Mulholland and then plunge down a precipitous slope. There's his house, clinging to the hillside. The first greeters are Shane, a German shepherd, and his pal Taby, an extremely companionable deer of four months. (A dear from Britain, girl named Sabrina, was also visiting Steve the day I was there, but she was gone for the afternoon.) There are cats all over the place. LIKES COMFORT Next, Steve appears in blue jeans, dirty shirt and bare feet — he's no beatnik, just likes comfort. He explains about Taby. It was found on a mountain road with rear end smashed by a car. Steve adopted it, had a vet fix its hind quarters with steel pins. Then the fish and game boys stepped in and said a deer couldn't be domesticated. "What was I going to do — set her free in the woods with six pins in her hips?" says Steve. "After a while, they sort, of dropped the matter." Taby, who is named for Colorado's Baby Doe Tabor, is recovered now, he adds, and is bandy around the house. Loves cigaret butts and cleans out all the ash trays. Only trouble: Taby drinks. It sneaks around at parties and takes sips from the guests' glasses. HAS FEATURES Steve wanders through the house, which is a normal California ranch-type with a 50-year-old slot machine and an ancient piano. Outside he shows the sunken bar he is building. It will house some huge whisky barrels, in which he plans to make his own wine. (Are there revenooers in these hills?) Then he ambles down the two-acre estate to his latest addition. It's a monstrous swimming pool with a tropical island in the middle. "The pool started out to be 48 feet long," Steve says, "but by the time I finished, it was 66 feet. I'm going to stock it with perch." Won't his female guests object to sharing the pool with fish? "The perch won't bother 'em," the actor says. "If the girls don't like it, they don't have to swim." IT'S A RESERVOIR The pool, which is classified as a reservoir for tax reasons, will eventually feature a waterfall flowing into it and a mountain stream continuing down the mountain. Cost of the project: $12,000. In another part of the grounds, Steve introduces two other pals, Gretchen and Heidi. Both goats, but one smells like a goat and the other doesn't. Then there is Girl, a Doberman Pinscher and mother of Shane's 10 puppies, as yet unnamed. [Sabrina and Shane] "Cats?" says Cochran. "I've got seven of them —10 at mealtime; three more wild ones come out of the brush. One cat is named Zsa Zsa — she's mean and unfriendly and won't eat with the other cats. She's a real cool cat." And so is a guy named Steve Cochran. |

Page Created: 2024-11-06

Last modified Friday, 13-Jun-2025 11:05 AM