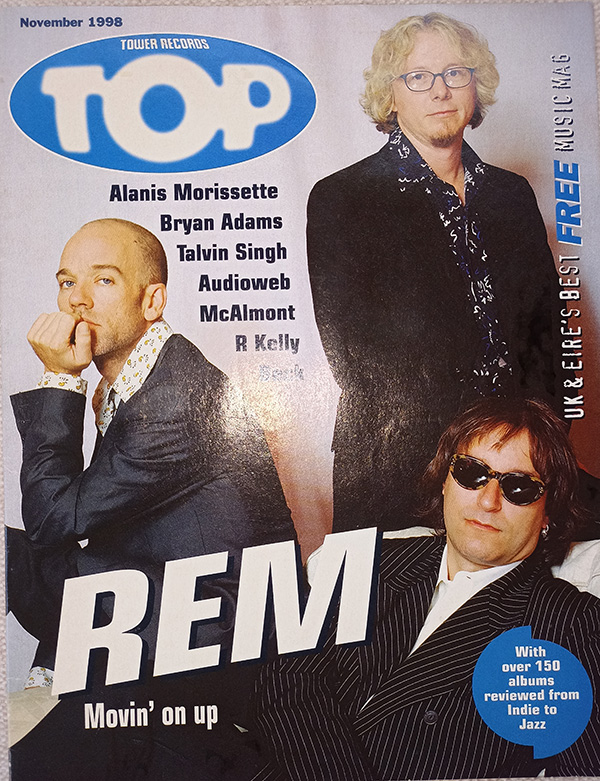

REM PRESS

Movin' on Up1998, November, TOP magazine

|

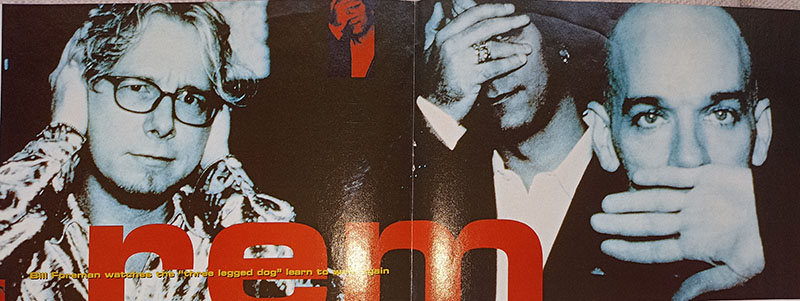

It's the end of the world as we know it: the doom mongers are conjuring up images of global power failures, frigid ATM machines and remote encampments of survivalist computer programmers devouring their own offspring. But REM fans have millennial fears of their own: December 31,1999 is the date that, on a number of occasions, Athens, Georgia's most beloved quartet claimed it would cease to exist. Of course, in one sense, that's already happened. A year ago, Bill Berry retired from REM. after 18 years service and a 1995 world tour in which a cerebral aneurism nearly claimed the drummer’s life; Given the examples of the Who and Led Zeppelin before them, it's understandable that the remaining members thought about calling it a day. Instead, Michael Stipe, Peter Buck and Mike Mills chose to forge on, reasoning that a three-legged dog is still a dog, it just has to learn how to walk again. So how's it going? Up, the newly-released album from the Trio Formerly Known As REM, answers that question and raises a few more. The record was — as records are — difficult to make," says Stipe, his voice floating above the murmur of New York traffic eight storeys below his hotel room. “This one was even more so because of Bill's departure. There was a feeling among all of us, almost a feeling of liberation—not so much from Bill and his input into the band and recording — but it really kind of blew the doors wide open. Whatever foundation we had to fall back on was gone, and so we were truly floating in space, bumping into each other over and over again, and creating some sparks." REM do all that and more on Up, an inspired left turn from a band that, by all rights, shouldn't have any left turns left. The group reaffirms its knack for reconciling apparent contradictions: Low rock meets high art. Cult band as pop phenomenon. Radical shifts that feel familiar. The new album is a lush affair, the guitar-rock sound supplanted by arcane keyboard and rhythm machine atmospherics that yield one of the most melodic yet challenging REM albums to date. “It's not that, by having a drummer, we felt boundaries, certainly not with Bill, who's a fantastic drummer," clarifies Stipe. “We simply couldn't find a fake Bill to come in and be him. And that wasn't the direction the record was headed in anyway. So it was truly an experiment on all levels, and I think we came out of it with something pretty spectacular." Asked if there was ever a point where he felt the experiment would fall apart, Stipe flashes a weary smile: “Six or seven times a day for six months.” On the status of everyone's favorite three-legged dog, Peter Buck echoes Stipe's excitement while amplifying the uncertainty. “I’m really happy with the record, but I'm not sure that we figured out how to be a band without Bill,” says Buck. “That's one of the reasons we’re not going to do a full-scale tour this year. We switched instruments a lot. I'm not sure how we'd play this stuff live. I mean, I played all the bass on the record, so am I now the bass player? Does that mean Mike’s the keyboard player and we'll have to hire a guitar player too? Laugh if you want, but it's kind of serious. Mike doesn't know the bass parts on these songs. We're in the process of figuring out what kind of band we are, what kind of band we’re going to be.” Buck likens Up to an earlier transitional album in which he set aside his Rickenbacker and, in that case, picked up a mandolin for a collection of songs that included the breakthrough ‘Losing My Religion'. “When we recorded Out Of Time, it was a matter of having been on the road for 10 years pretty much solid, probably at least a thousand dates in that time period, and just going, 'Gosh, you know, I don’t want to sit down with an electric, guitar and a drummer going boom-chicka-boom-chicka-boom.' I wanted to approach songwriting and performing differently. “This record was really similar. Bill was gone. We didn’t have a drummer. A lot of what we did was build percussion loops or use my old drum machines. And I remember at one point on the third or fourth day, Mike was saying, ‘Gosh, you know, I just really don’t wanna play bass.’ And I love playing bass. One of the secrets of rock 'n' roll is that every guitar player wants to play bass and every bass player wants to play guitar.’ “I’m the bass player, I'm still the bass player, I’m always gonna be the bass player,’ says Mike Mills with the resigned grin of someone who, after all, has been the bass player since REM began rehearsing in a converted Athens church 18 years ago. “But I’m not just the bass player." Indeed, Mills’ multi-instrumental and composing talents are more in the foreground than ever now that Berry is gone. “We figured on that last record, New Adventures in Hi-Fi, we had done the drums, bass and guitar thing about as well as we could do it,” says Mills. “I'm not saying it’s the best record we'll ever make. But in terms of approaching the next record, we just really didn't wanna sit there and play that traditional lineup. And so going into this record, we were getting Bill to experiment with rhythm sounds and drum machines and loops anyway. So when he left, it just amplified the process.” Of the three remaining REMs, Mills has worked longest with Berry. Back in Macon, they played together in everything from high-school marching bands to wedding combos. But, he says, they rarely followed standard operating procedure as a rhythm section. "I wasn't locked into the drummer in the traditional sense where the bass player plays the root note of the chord on the same beat as the kick drum plays. I never did that. I didn't know I was supposed to do that, for one thing. But I also just never wanted to. I always played more of a melodic bass, more like a piano bass. So in that sense, we weren't so locked together that I’m unable to play with anybody else. As far as the future, I don't know. Much as I hate auditions, we had to do a few and [Beck sideman] Joey Waronker is a great drummer. If we end up playing with him, that will be fine.” Temporarily liberated from his four-string companion, Mills indulged in an array of decades-old machines chosen for their pre-digital warmth and unpredictability. “We had 14 different keyboards in the studio, everything from a Hammond organ to an old ARP synthesizer that didn't really work very well and a Moog and a piano and a thing called the Kitten and a Baldwin Discoverer. We wanted this record to have a lot of weird sounds on it that you hadn’t heard before, sounds that might just come in for a minute on the song and go away. "As for drum machines", Mills says, “there’s one built into the Discoverer that we used, and there was an old Univox that doesn't really keep straight time. Just whatever Peter had." The band's determination to experiment has apparently been unaffected by the reported $80 million contract Warner Bros, drafted to keep them on board. On the whole, Up is less aggressive sounding than its predecessors, a change that's in large part due to the revamped instrumentation. Is the band's label happy with the idea of a record that rewards patience? “What do you think, that they want one that you get the first time you hear it? Because if you get a record the first time, that usually means that you hear it about four times and then you put it away and never listen to it again.” True enough, though it could be argued that most record companies today would be fine with that. “Well, I think everybody kind of knows what we are at this point. I mean, they're not looking for the hit of the month out of us." While REM continues to work with guest musicians (Waronker lends a hand on Up, as. do drummer Barrett Martin and multi-instrumentalist Scott McGaughey of Buck's side projects Tuatara and Minus 5], the method of recording has significantly changed, “Normally you go in the studio, you get your drum sound, get your guitar sound, and then you record the basic tracks with guitar, bass and drums," says Mills. “But since we didn’t have Bill, we didn't want to record that way. So we would start with a drum machine or a guitar and just build songs up like that. So there are very few songs where we’re actually all playing together at the same time. If you had an idea, you could run in there and put it down." The composing process, on the other hand, remains much the same. “Since Peter and I live so far apart, we tend to write individually and then when we get together and rehearse, we show each other the songs and then we do ’whatever it is we do to them. We don’t write lyrics, so whether Michael's lyrics are things that he has in his notebook or whether they are things that he comes up with after he hears the music, which is usually what happens, either way the lyrics come after the music.” Mills cautions that his interpretations of Stipe's lyrics may be no more valid than anyone else's. “I think it is very much an introspective, reflective record, especially in the sense of the characters. What I see is a bunch of characters in the songs who are taking stock of where they are. They've found themselves in these weird situations and they’re thinking: How did I get here? And what am I gonna do now that I'm here? “It's not like Michael's having a big midlife crisis, because so much of what he does is writing from characters' points of view. When Michael sings "I", a lot of people think it means 'I, Michael Stipe'. And it doesn't. It means ‘I, the character in the song'." Bill Foreman is senior editor of Pulse! magazine |

Page Created: 2023-11-10

Last modified Wednesday, 15-Nov-2023 10:45 AM