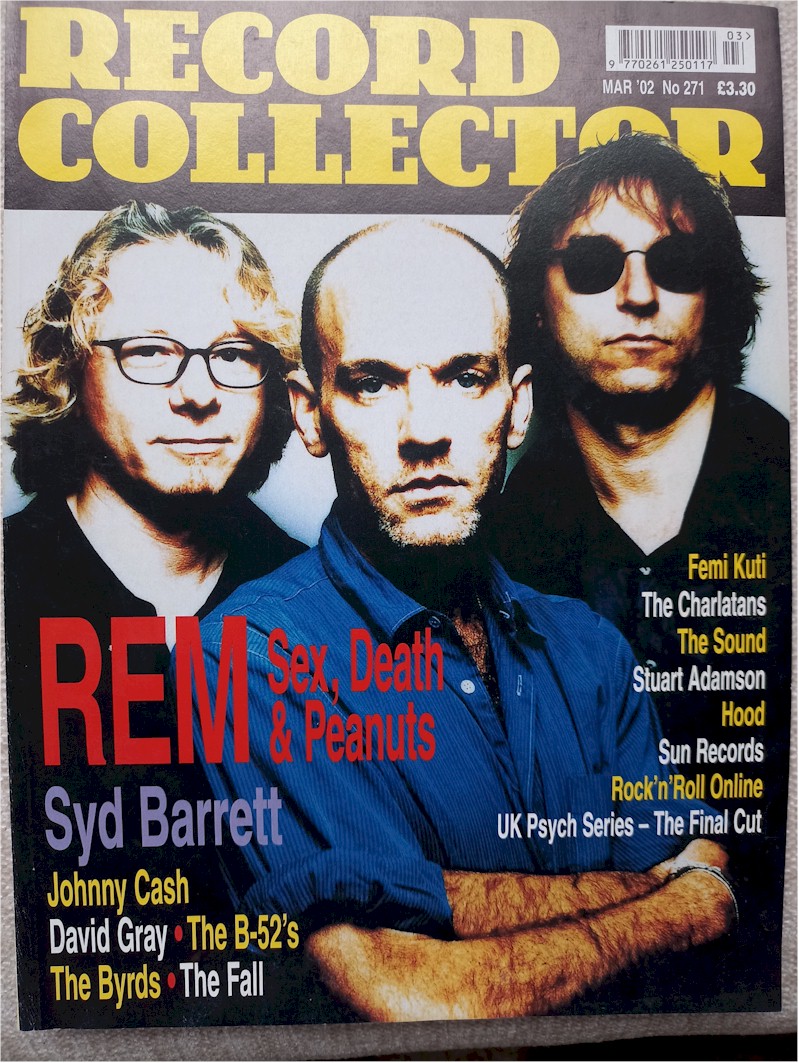

REM PRESS

Sex, Death and PeanutsRecord Collector (UK) 2002-03-00, issue 271 |

|

|

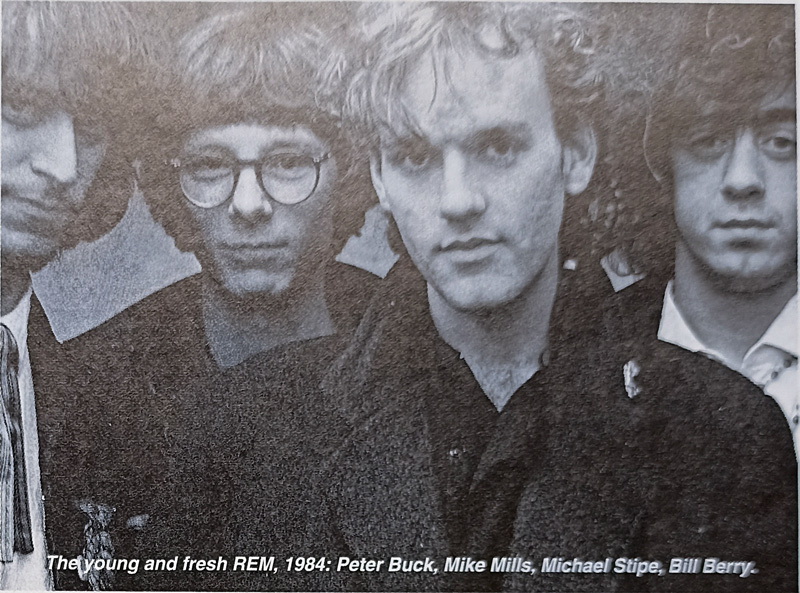

FROM THEIR HUMBLE BEGINNINGS TO 'THE GREATEST BAND IN THE WORLD’Nowhere does the fickle finger of fate wield more influence than in the field of popular music. Bands come and bands go, often without any clearly discernable rhyme or reason to their arrival and passing. Perhaps the only certainty is that, sooner or later, even the most durable of outfits will be but a memory in the minds of its fans — which means that how a band’s career progresses, rather than for how long it lasts, is the key point.And there are a few instantly recognisable career paths a group can follow. Look at the Sex Pistols: one album, some tabloid headlines, and then nothing for 19 years. What about U2 and Madonna? Both acts rose high in the 80s and struggled through a patchy 90s — but went on to conquer their demons and ascended to the very top of post-millennial pop. Up and down, down and up — what very few acts can expect is a career without unexpected highs and lows. But then we have REM. The career of the Athens, Georgia foursome — first formed in 1980, which means that they recently celebrated their 21st anniversary — can be best described as a long, gentle parabola. For REM, the 80s were all about College Rock: that very American, slightly dull-sounding guitar music that entertained a small but devoted fanbase Stateside, and which many a music journalist described as The Next Big Thing (except it never was). Those years were good ones for the band: as big fishes in a small pond, their future looked bright, although it seemed that no one outside the college campuses would ever pay them much attention. For a good few years, REM were the cool name to drop, as misunderstood as they were lauded. They were very much a storm waiting to break, like thejr English counterparts, the Smiths, or perhaps Lambchop nowadays. But then Out Of Time (1991) and Automatic For The People (1992) saw REM blow up to the wholly unforeseen status of Biggest Band In the World, courtesy of a clutch of seminal singles including the shiny, happy ‘Shiny Happy People’ and the subtler, melancholic sounds of ‘Losing My Religion’, ‘Drive’ and 'Everybody Hurts’. While grunge wailed, house mutated and hip-hop diversified, REM’s gentle, affecting melodies laced with singer Michael Stipe’s obscure-but-memorable vocals ensnared a whole generation of listeners, who bought into the REM formula with enormous enthusiasm. Their long-standing die-hard fans could only watch aghast, as ‘their’ band became public property — followers of Nirvana had found themselves in a similar position after the world wide impact of Nevermind, of course, but you try telling that to a true devotee of Fables Of The Reconstruction or Life’s Rich Pageant.

FOR A GOOD FEW YEARS, REM WERE THE COOL NAME TO DROP For a couple of years it seemed that REM would stay at the top of the rock tree, with Stipe evolving into a style-mag staple (his determined privacy and sexual ambiguity made him even more popular) and guitarist Peter Buck becoming revered as the ultimate musician’s musician. But the glory years didn’t last long: the Automatic follow-up, Monster (1994), was a self-declared return to REM’s guitar-slinging roots, and while ‘What’s The Frequency, Kenneth?’ made it to No. 9 in the UK, the concept of REM as rockers didn’t sit well with many music buyers. Brows began to furrow. An unspoken hope that Buck would once again get his mandolin out for the next album began to grow among observers, but this was not to be: 1996’s ‘road album' New Adventures In Hi-Fi was neither fish nor flesh, disappointing the newly-converted but also failing to satisfy the old school. Even the Patti Smith-assisted ‘E-Bow The Letter’ — which made No. 4 over here — wasn’t exactly awe-inspiring. Drummer Bill Berry departed the following year after surviving a brain aneurysm on-stage, and in doing so deprived the band of much of their pop awareness: 1998’s Up was hailed as a new experimental success on its release, but the plaudits didn’t seem to boost the album’s merely-adequate sales. And so REM’s gentle decline (in commercial, not critical terms, it should be stressed!) continued until 2001, when their latest album, Reveal, was greeted with genuine praise. Proof-of-pudding was demonstrated when the album went on to become the band’s biggest seller since the far-off days of Automatic For The People going straight to No. 1 in the UK. Fans and press have been somewhat rejuvenated by Reveal's popularity, and the atmosphere surrounding the band is more optimistic than it has been for several years. What better time, then, to look back at the remarkable career (both pre and post-AFTP) of this unique band? Your ever-reliable RC [Radio Collector] has compiled 21 moments (plus a few bonus treats tor good measure) in REM’s history — one for each year of their existence — that remind us of just how godly they have been, whatever the Zeitgeist may say. Read on overleaf, as we Reveal all.... Joel McIver

|

1 Murmur (album, April 1983)

|

2 ‘Don’t Go Back To Rockville’ |

3 ‘Can’t Get There From Here’ Surely the highlight of the criminally undervalued Fables Of The Reconstruction. Uniting them with legendary folk-rock producer Joe Boyd, the album was recorded in London’s Wood Green during a grim winter (Mike Mills: “It was freezing cold, we didn’t know a soul, the food sucked"), but turned its attentions fully on their native Deep South. Thus the combination of production bleakness with sharply-focused songs (Buck: “it’s a misery album in a lot of ways, but the songwriting’s great”). What Buck calls a ‘jazz ballad’ matched a funky guitar line to Stipe’s deadpan deep vocal (“I was trying to sound like Mahalia Jackson!”), frenetic falsetto backing vocals from Bill Berry, and a full-throated horn squall at the end. Its failure to hit the charts mirrored the album’s low profile. As Buck remembers, “It’s like a tongue-in-cheek tribute to Ray Charles and James Brown and all the other Georgia music greats”. |

4 ‘Superman’

to be continued 2023-11-21 |

Page Created:2023-11-20

Last modified Tuesday, 21-Nov-2023 12:16 PM

Please tell me of transcription errors or other site screwups